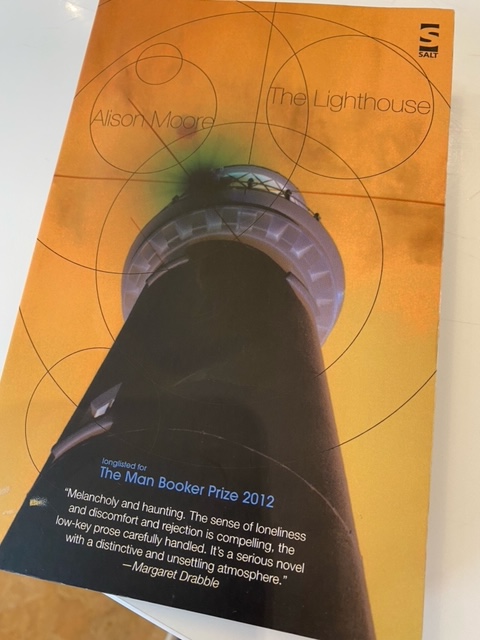

Book review: ‘The Lighthouse’ by Alison Moore

“Do you ever get a bad feeling about something?”

This sentence, which opens chapter three of The Lighthouse, could be the by-line for the book.

I got this book around the time it came out in 2012, when it was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. I put it aside after one or two chapters, finding it too depressing.

Recently, nine years later, after coming across it again during a house move, I gave it another go. This time, I made it to the end.

That’s not to say that it’s not still depressing. It is. This is a very weird book that makes you want to keep turning the pages despite the fact that it is about loss, abandonment, hopelessness, pettiness and apathy. Whether it’s a literary achievement to keep the reader turning the pages because they simply can’t believe that the story will stay so bleak, is another question.

A quick summary: Futh is a recently separated, middle-aged Englishman who undertakes a week-long, solo walking tour along the Rhine in Germany. This trip is the backdrop for his ongoing ruminations about his past. His mother left when he was a child, his father was an unfeeling cad, his only friend drifts away, his wife leaves him. During his trip, he repeatedly revisits these painful memories, turning them over and over, examining them from all angles, teasing out their excruciating details.

The first thing to say about Futh is that his odd name embodies his entire character. He has no first name, an oddness that suits him down to the ground. Also, it straight away reminded me of the words ‘futile’ and ‘futility’.

The other main character is Ester, the landlady of the B&B he stays in on his first and last nights in Germany. She, too, is treading water in life, mired in hopelessness, bleak memories and an equally bleak present.

The ending of the book is ambiguous, but it’s not a spoiler to say that it’s not a happy one whatever way you look at it.

So what kept me reading?

Moore is a highly accomplished writer who skilfully uses prose to conjure up a world characterised by minute, mundane details. Futh’s thoughts and actions are described step by painful step, as in this scene on the ferry on his journey to Germany:

“Turning off the shower and stepping out of the cubicle onto the non-slip floor… He leans against the sink area, wipes his hand over the steamed-up mirror and looks again at his reflection.”

…and, later in the book:

“Futh notices that his feet are burnt. The skin is hot and pink between the straps of his sandals, and still blue-white underneath the straps, like the perfect band of pale skin on a ring finger when a wedding ring is removed for the first time in years.”

The effect of this level of detail on the reader is claustrophobic, grinding, relentless. You realise that this is how Futh himself must feel every day. However, it also makes you want to read on, hoping that some relief, some escape, is coming, for both yourself as reader and the hapless Futh.

Moore also uses the relentless detailing of mundanities to good effect when she describes food. Throughout the book, food is depicted as tasteless and unattractive. Futh’s first meal on arriving in Germany is a clingfilmed plate of cold cuts, dried out due to his late arrival. Futh also has difficulty acquiring food; several times on his trip, he misses meals; it is one of the many areas of life in which he is ineffective, joyless.

Equally unsettling is Moore’s depiction of the body. Her bodies are pasty, sagging, unappealing. We are reminded on a few occasions that Ester’s figure has deteriorated and is unattractive (her husband even points this out at one point); Futh’s body is barely functional enough to get him through his walks each day: his feet become raw and blistered, his skin burns in the sun. When Ester is about to get into bed with a customer of the B&B, the man’s exposed body reminds her of “sausage and sausage meat”.

The Lighthouse is full of recurring images and themes. The chapters are named after them: ‘Oranges’, ‘Smoke’, ‘Venus Flytraps’, ‘Beef and Onion’. The main and most obvious image is the lighthouse, both an actual lighthouse of a childhood holiday of Futh’s and two perfume bottle holders in the shape of lighthouses. There is also the B&B and the town it is in, both named ‘Hellhaus’, which, we are told, means “bright house or light house” in German, but sounds horrifying in English.

The lighthouse image recurs repeatedly throughout the book, but cruelly inverted: what should be a symbol of safety and guidance is actually ominous and treacherous. Likewise, the B&B, instead of a place of rest and sustenance, is unwelcoming and uncomfortable in every way; the lighthouse Futh saw on his childhood holiday was, according to his father, responsible for many shipwrecks; the perfume bottle holder that Futh carries with him does not protect the bottle from getting broken or Futh from being cut by the shards.

Then there are smells. As the chapter names above indicate, smells are prominent in the book, all of them reminding Futh of various losses and betrayals: cigarette smoke, violets, oranges, disinfectant, camphor. We learn that both Futh and Ester have a professional interest in smells; Futh states early in the book, “I work in the manufacture of synthetic smells”, while Ester, when she was younger, wanted to become a perfumier. What the significance of these facts is, I’m not sure. Since it’s synthetic smells that Futh works with, and Ester did not realise her ambition, perhaps they’re simply intended as further instances of failure and falling short.

The subjects of family, marriage and parenthood are, like the lighthouse symbol, inverted in the book to epitomise their opposites: absence of love, physical absence, dissolution and betrayal. Futh’s mother left him; his father is uncaring and cold. The marriages in the book – Futh and Angela, Futh’s parents, Ester and her husband, Ester’s brother-in-law and his wife – are loveless. There are multiple instances of adultery. Pregnancy is depicted consistently as a negative: Futh seems unbothered by his wife’s many miscarriages, which are mentioned in a dry, emotionless tone; Futh’s uncle “got a girl in trouble” and had to leave home; Futh’s father says that a man’s life is over when he marries and has children; it is hinted that Ester had an abortion.

As for love outside of marriage, the subject of Futh feeling any kind of affection is mentioned only once when we are told that he is “rather fond of” his pets. What are his pets? A collection of stick insects.

Futh repels people; he has no friends; his life is of benefit to no-one. His existence is truly futile.

It remains only to wonder, as one reviewer on Goodreads wrote: “I’d really like to know what a writer’s motivation is to write something like this.” Maybe that’s a little harsh: as I said above, the writing is clever and considered, and the novel is carefully worked out and well structured. There is pleasure in reading good writing.

I’m glad I read The Lighthouse, but I’m also glad it was short.

Book review: Jojo Moyes, ‘The Giver of Stars’

Jojo Moyes, as the cover of this book tells us, is the author of the bestselling ‘Me Before You’, which was made into a successful film in 2016. So expectations were high for ‘The Giver of Stars’, her sixteenth novel.

I was drawn in by the blurb, which begins “Alice Wright marries handsome American Bennett Van Cleve, hoping to escape her stifling life in England”. Adventure and conflict, two key elements of story, are there immediately. And the book delivers on this promise from page one. The prologue depicts a woman on horseback in the woods who meets a threatening stranger. A frightening encounter ensues and the woman only barely escapes. We are left with an air of tension and mystery: who is the woman, why was she alone on horseback, and not least, why does she have a heavy book with her?

The prologue also gives a hint of what is to be a key theme of the book when we are told, “And there is the bare truth of it, for her and all the women around here. Doesn’t matter how smart you are, how clever, how self-reliant – you can always be bettered by a stupid man with a gun.”

The main story then switches to the viewpoint of Alice Wright, newly arrived in the town of Baileyville, Kentucky, in 1937. The author has a lot to do in the first few chapters to ensure that readers quickly accept and relate to the whole cast of characters, the locale, and the era. This is no small task. Moyes handles it deftly in a number of ways.

First off, to conjure up a vivid picture of the locale, she uses slang, idioms and accents in the dialogue that are universally recognised (whether accurate or not is another matter) as belonging to the Appalachian region of the USA. She uses just the right amount of “ain’t”, “ole” and “git fast”; she doesn’t overdo it. (When talking about accents in books I always think of the character of Joseph in Wuthering Heights, whose speech was so twisted by Bronte’s attempts to reproduce his accent that the character was basically incomprehensible.)

Secondly, she uses well-known historical references – such as to the Depression, President and Mrs Roosevelt, the mining industry and poverty in the area – to situate the story in the period in question. The position of women in society at the time is brought up just a few pages in. The reactions of the townsfolk to the proposal to set up a mobile library run by women reflects the mixed views of the time.

No story set in the USA can overlook the issue of race. Moyes tackles it cleverly. There are black characters: two among the main characters, as well as the many local black men who work in the mine. These characters are constrained by the social norms of the time: Sophia Williams previously worked in the ‘Colored Library’ in the nearby town, her brother worked in the mine, and they now live in poverty in a tiny cabin. Sophia is welcomed and accepted by the other women who work with the mobile library, but her role is limited to that of administrator; she doesn’t go out distributing the books on horseback like the other (white) women, and she doesn’t like to be seen at public gatherings. Sophia herself accepts these limitations uncomplainingly and while some of the other women murmur against the injustice, the status quo is never actually challenged within the narrative.

This general acceptance by the characters of racial inequality jars a little for contemporary readers. However, as well as reflecting the views of the time, this ring-fencing of a sensitive issue is also characteristic of the genre. To confront and deal with difficult social and historical issues is not in the remit of romance novels. Given the constraints of the genre, Moyes deals with the issue of race competently and in a plausible way.

A main theme in The Giver of Stars is women’s empowerment through sisterhood. Moyes open this topic straight away by depicting the establishment of the town’s mobile library, run by women. Sisterhood comes from the top; we learn that this is a nationwide initiative championed by Eleanor Roosevelt. Alice, badly let down by the men in her life, finds acceptance, fulfilment and a new self-confidence in her work with the all-female operation. Its success in bringing literacy and enjoyment to the isolated poor people of the area is due in no small part to the solidarity and mutual support of the library’s staff. Moyes nicely juxtaposes this success with the toxic, destructive, male atmosphere of the mines. Growth through female solidarity is also illustrated in the fact that Izzy Brady learns to work with her physical disability and to stop regarding it as a fatal weakness.

There are good men in this story, though. It’s amusing that the two main “good” men are the sexy ones, Sven Gustavsson and Fred Guisler. This division is further reinforced by the depiction of the Van Cleve men as repressed and puritanical; Bennett cannot engage sexually with Alice, while her growing affection for Fred culminates towards the end in the longed-for act of lovemaking.

Women taking control of their own sexuality is yet another theme in the book. A banned (in the USA) work of the time, Married Love by Marie Stopes, is passed around among the women of the area in a further example of empowerment through sisterly solidarity. Alice’s own sexual awakening, which runs in parallel to her progress towards self-fulfilment, is shown to be another outcome of literacy and education.

This being a novel, there has to be a crisis. The shocking developments that occur about two-thirds of the way in are unexpectedly harsh and gritty. Previously strong bonds are tested to their limits, characters crack under pressure, and the dark underside of a misogynist society is revealed. Moyes brings everything back successfully at the end, order and harmony are restored, and the values espoused by the book – sisterhood, education, literacy, empowerment – are shown to be victorious.

I highly recommend this book as a great, rollicking story well told with equal measures of humour and grit.

‘Normal People’ by Sally Rooney: book review

The first thing to say about this book is that it has won a clutter of literary awards, as the back of the book tells us.

I don’t think I have ever simultaneously enjoyed and disliked a book so much.

The main characters are painfully annoying and endearing at the same time. Marianne and Connell are a modern version of the star-crossed, “from opposite sides of the track” trope. (Not that they are really a couple, as we are all-too-frequently reminded. They are on-again-off-again throughout the story with irritating frequency.)

Marianne and Connell get to know each other because Connell’s mother is a cleaner who works in Marianne’s palatial house. This income gap is beautifully drawn in little details such as “[His mother] put a box of own-brand cornflakes in the press.” The two main characters first connect as teenagers in the kitchen of that house, in an interaction that is well crafted in its adolescent awkwardness and hiatuses. From this point on, chance meetings over several years see them repeatedly disconnecting and reconnecting.

Marianne’s world is privileged and rotten. She is the broken product of that world. Connell comes from a working-class, single-parent family managing in straitened circumstances. He is handsome, and appears confident, well-adjusted and popular.

The pair deal with such painful issues as physical and psychological abuse within families and relationships, class tensions, depression, self-loathing, isolation, alienation, loneliness in the young … the list goes on. It becomes increasingly clear as the story goes on that these people are damaged, possibly irreparably. That’s fine; damaged characters are the lifeblood of novels. The problem arises when you realise that they are not going to change.

There’s a lot to love in this book: the nuances of the conversations and emotional dynamics between the two characters are incredibly well observed. As she did so successfully in her 2017 smash hit debut, Conversations with Friends, Rooney uses extreme detail on facial expression, thought and movement to illustrate the tiny, unspoken shifts that characterise a relationship. For example, this section when Connell works himself up to telling Marianne that he won’t be staying Dublin for the summer:

“Yeah, he said. I’m going to have to move out of Niall’s place.

When? said Marianne.

Pretty soon. Next week, maybe.

Her face hardened, without displaying any particular emotion. Oh, she said. You’ll be going home, then.

He rubbed at his breastbone then, feeling short of breath. Looks like it, yeah, he said.”

Rooney also excels at pacing (in part, using the movement and facial expression referred to above) and at subtly showing time both passing and appearing to stand still. This sentence stands out for me: “They are driving past the football grounds now. A thin veil of rain begins to fall on the windshield, and Connell turns the wipers on, so they scrape out a mechanical rhythm on their voyage from side to side.”

The people who populate Marianne’s moneyed world are drawn as despicable in various ways. Their characterisation is well executed; we are intended to detest them and we do.

A minor but viscerally affecting aspect of the book is how Rooney depicts the time wasted in school life. This is beautifully drawn in all its pain: “It stayed dry for the match. They had been brought there for the purpose of standing at the sidelines and cheering” (page 11).

However, these micro-details of Rooney’s often miss their mark. If you’re going to describe someone deciding not to take off their coat because they’ll be leaving again in a minute (page 185), it needs to be necessary; it needs to move the narrative forward. Otherwise, it’s just boring.

Another gripe I have is that we are never given any proper insights into the source of Marianne’s unpopularity in school. We are told that she wears terrible shoes, is seen as ugly, wears dirty clothes, doesn’t wear makeup, doesn’t make any effort with her appearance. We are given to understand that these things are at least part of the reason for her lack of friends. She is very clever and doesn’t hide it; she doesn’t court popularity. But none of this is enough to explain the degree of ostracisation and meanness that she is subject to by her school mates. Since their time in school occupies a good part of the book, it is fair to expect more depth on this aspect of Marianne’s character. It would have made for a more coherent narrative overall.

As for Connell’s character, he ignores Marianne in school along with the others. We are never told explicitly, but we are given to understand that he wants to avoid being tainted by association. This streak of meanness in him – vanity even – is never satisfactorily incorporated into his character throughout the rest of the book. He fares somewhat better on the character development front in that he eventually goes to therapy. He doesn’t seem to benefit from it, sadly.

Another open question is, when they get to college, how do their roles become reversed? Marianne is suddenly popular and beautiful, while Connell is friendless and alone. This new dynamic is referred to but not substantially backed up. Not only that, but despite their new relative popularities, nothing changes in their relationship; she is still subservient, he still dominates.

Speaking of which, one of the things that kept me from warming to Marianne is her unchanging submissiveness, to Connell and others (which in a later stage of the book leads her into a violent and humiliating situation). I say unchanging because we expect character development in a novel. Marianne does not grow or mature. She literally says as much herself in the second-last sentence of the book: “I’ll always be here.” Nothing has changed from when we first met them.

The second-last paragraph seems to be an attempt to tie things up in a bow and convince us that there has been character development: “They’ve done a lot of good for each other. Really, she thinks, really. People can really change one another.” However, for this to be stated explicitly doesn’t mean it has actually happened here.

There is a sort of climax in the novel, but it’s so understated, and not entirely news, that you might miss it. There’s nothing to spoil about the end.

In her outstanding talks on writing, Claire Keegan has said (I’m paraphrasing) that the writer has a contract with the reader, and the writer must fulfil that contract. In other words, if we see a smoking gun during a story, we must be told what happens to that gun (this principle is also known as “Chekov’s gun”). Similarly, if a writer sets up two characters with a problem (that they can’t connect properly despite loving each other), something must happen to resolve or at least change that problem. This contract is not honoured in Normal People.

Big sums in headlines come at a cost: accuracy

When a big financial award is made by the courts as compensation for injury due to negligence, why are the headlines always about the amount awarded?

December 19, 2019

December 6, 2019

Note the wording in the second headline above: the boy has “secured” the money; he is positioned as the active party; the tone of the headline suggests that he pursued the money, that the motivation was financial gain.

Rather, the awardees in these types of cases are the passive party. By that I mean that they are the ones to whom something was done, they suffered at someone else’s hand; they are the victims.

To highlight the amount awarded creates the impression that these cases are all about the money, when in fact we know that award payments are used to pay for medical care and other care the person may need – in many cases, for the rest of their lives.

November 5, 2019

What’s more, by focusing on amounts, the wording of these headlines paints a picture of the complainants as grasping, greedy even. It creates an implicit link between these cases and the Irish phenomenon of ‘compo culture’, when in fact, the two are not connected.

The term ‘compo culture’ refers to a practise of false, vexatious claims (often insurance claims) intended to illegally enrich the claimant. The cases I’m talking about in this post are anything but false or vexatious.

The only vexatious thing about them is that the complainant, who has already been wronged, usually has to fight their way through the courts to get justice. (This article quotes a victim’s father: “Unfortunately, it took 6 years, and a court case, for the HSE to admit liability.”)

Editors in the news media know what they are doing here. They know that large sums of money in headlines catch the eye. In these days of fleeting attention spans and countless competing sources of news, there is pressure to create attention-grabbing headlines.

But let’s keep out of it kids who will need 24-hour care for the rest of their lives, or parents bereaved due to a mismanaged birth. Let’s shift the focus to the real wrongdoers: “HSE pays bill for doctor’s medical negligence”. “Child’s family compensated for botched birth.”

It’s not hard to write catchy headlines that tell the truth.

Sources:

https://www.irishtimes.com/news/52-500-medical-negligence-award-1.97289

https://www.rte.ie/news/courts/2019/0725/1065235-rachel-cooney-high-court/

New Halloween story

What is it about children that has so much creepy potential? Last week, I was in a bit of a sweat trying to come up with a scary story for an event on Friday evening. At first, no ideas would come. Then, a few came, but they all involved children. As a mother, I felt resistance to writing about children in creepy situations. I tried to come up with something that did not involve children… to no avail. I finally gave in.

Here it is, my Halloween story for 2018.

Shadows still remain

“I’ve heard stories about this place,” said my mother.

The house had a wooden staircase that creaked. I stepped up and down, up and down, listening to the creaks and eavesdropping as my mother and the estate agent talked in the hall below.

“That’s just what they are – stories,” said the estate agent. “After the woman died, the DA had forensics come in, search the whole house. There’s nothing here.”

They moved into the kitchen, out of earshot. I headed up the stairs and wandered aimlessly from one empty room to another. After months of house-hunting, I was bored rigid. Every place in our price range had the same crap: yellowed newspapers, stained carpets, shoeboxes of receipts. Once, I got lucky and found a one-legged doll. The estate agent said I could keep it. Back at the motel, Mom threw it in the trash.

I went into one of the bedrooms and stood by the window, overlooking the back yard. Mom and the estate agent were down there, gesturing and talking. The yard was just as sparse as the rest of the place: bare, uneven concrete with weeds poking up between cracks. Rain started to fall, spattering the concrete with grey. The adults moved inside, out of sight.

Then I saw something. The grey blotches being formed by the rain weren’t all random. Some of them, close to the perimeter wall, were roughly rectangular in shape, all of similar size. I counted six of them, three by the side wall, three by the back wall.

I heard voices downstairs. I went to the landing and looked down. The estate agent was gathering up her keys. Mom looked up at me, wearily.

“Come on, Tricia,” she said. “Bus’ll be leaving in a minute. Put your hood up.”

I snuggled up to Mom as we sat side by side on the bus. She looked down at me in surprise.

“You all right, Trish?” she said. Dark was falling outside now, trees and buildings trundling past in shadows.

“Don’t rent that house, Mom,” I said.

I felt the rise and fall of her body as she sighed deeply.

“I won’t, sugar. Something there not right, no matter what that estate agent says.”

I nodded into her sleeve, shutting my eyes tight.

(c) Orla Shanaghy 2018

Kerrie Hardie liked my trousers; Imagine Arts festival 2018, Spokes, and Culture Night 2018

It’s been a busy month on lots of fronts, including literary events in Waterford. The biggie in October is of course Imagine Arts Festival, which has just finished. I read a new piece of mine at the ‘Modwords at the Parlour’ event, held in the Parlour Vintage Tea Rooms and organised by Anna Jordan, which was part of Waterford Writers’ Weekend, which in turn is part of the Imagine festival (keep up).

Reading a new Halloween piece at ‘Modwords at the Parlour’, part of Imagine Arts Festival, October 2018

I couldn’t believe I had never been inside the Parlour Vintage tea rooms before. It feels like my spiritual home: quirky, arty, casual, and serves WINE AND CAKE. I plan to move in soon.

I read a new short Halloween piece, which will be published here tomorrow!

Earlier in the month, I was asked to participate in Spokes, a new(ish) monthly reading event organised by well-known writer and journalist Colette Colfer. This was super-exciting because the guest reader was none other than Kerrie Hardie, one of Ireland’s most celebrated poets. Kerrie read several of her poems, which were a joy to listen to. I got to speak to her but was so star-struck I forgot to get a photo! She admired my trousers! (And my work, in the dedication she kindly wrote in the book I bought.)

Mark Roper, another poet of national renown, was in attendance, though with his customary modesty he didn’t read, even though he has a new book out.

Reading at ‘Spokes’ literary event, October 2018

And at the start of the month we had Culture Night, an annual event, organised by the unstoppable Anna Jordan, Waterford’s arts queen at the moment. I read at an event in The Fat Angel, Waterford’s newest wine bar.

Reading at events is lovely. I plan to do as much of it as possible from now on. Preparing for reading at events is miserable… it’s a tsunami of all the usual writer neuroses and emotions… self-doubt, procrastination, resolving to pull out of the event, shame at the thought of letting people down if you pull out, more self-doubt, self-blame at committing to the event… But it all comes good in the end.

My letter to Mrs. Bennet broadcast on national radio

It’s important to acknowledge successes as well as failures in writing. (There are enough of the latter, after all.) So I’m very happy to report that an extract from a piece of mine was broadcast last Saturday on ‘The Book Show’ on RTÉ radio, Ireland’s national broadcaster.

Over the past few months, The Book Show ran a contest in which they invited listeners to write a letter to a character from a novel. Ireland’s Fiction Laureate, Anne Enright, picked a winner from the shortlist.

The entry that I submitted was a letter to Mrs Bennet from Pride and Prejudice. The show’s producer tells me that they received a huge number of letters to Pride and Prejudice characters so I am extra-pleased that mine was selected for reading. (See the end of this post to read my entry in full.)

A special episode of The Book Show was recorded in front of a live audience in Dublin’s Smock Alley Theatre on October 21st, and the recording was aired on October 28th. At this event – at which presenter Sinéad Gleeson also chatted to Anne Enright and fellow authors Lisa McInerney and Paul Howard – the shortlisted and winning entries were read by professional actors Derbhle Crotty and Dermot Magennis.

Mrs Bennet, played by Alison Steadman in the BBC series ‘Pride and Prejudice’ (1995).

The winning letter was written by Aoife Kavanagh, who wrote a letter to Holden Caulfield from JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Congratulations to her!

You can listen to the show here. My piece begins at 0:23:20 and the winning entry begins at 0:49:34 – but I urge you to listen to the whole show, there is some great work and super-interesting writerly discussion in there.

Lastly, here’s my written piece in full. Hope you enjoy it.

***

A letter to Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Dear Mrs Bennet

I see you standing at the breakfast room window. Your hand shades your eyes against the morning sunlight. A group of young women with cloaks billowing walk down the drive on their way into Meryton town. Their laughter reaches you across the crisp Hertfordshire air. Wrought-iron gates creak and your daughters disappear down the stony road.

Mrs Bennet, your husband’s surname is the only name we know you by.

You were once a slender-waisted Miss Gardiner, daughter of the town’s lawyer and celebrated beauty. You fell in love with a soldier. In your mind’s eye, you still see his red coat and brass buttons.

The redcoat left for the Napoleonic wars and you found love again. Mr Bennet was handsome, with a country estate could be inherited by sons only. Your mother’s satisfied nod on your engagement day assured you that those sons would come.

What your mother’s look did not say was that they might not stay.

The first pains came after a few months of marriage. You lay on your side in your bed, knees drawn up with cramps. Your maidservant, a girl of seventeen, wrung her hands in the doorway. You screamed and she ran for the housekeeper. Later, the maid carried away bundled-up sheets, the fabric pale against your scarlet blood.

It happened again, and again. You started to recognise the stabs in your abdomen. You had the housekeeper arrange a bedroom in the farthest corner of the house. More scarlet sheets.

When you reappeared downstairs after these absences, you could not bear the pain in your husband’s face. You began avoiding each other’s eye.

You grew nervous, agitated. What had they looked like, those ghost babies? Desperate, you bullied your maidservant into revealing that the sheets – too badly stained to wash – and what they contained were taken to a corner of the farm’s remotest field and burned. Thoughts crossed your mind of sneaking down there. But what would you look for?

You taught yourself not to think about the corner of the field.

The living children you finally bore brought you both joy, even though they were girls. In one way, the curse seemed to be broken. The wet-nurse looked askance as you took the babies from her, wanting to feed them yourself. You came to life again.

But you learned to dread the look on the midwife’s face. You would let your head fall back onto the pillows, willing her to say the word that would secure your family’s future prosperity. It never came.

By silent, mutual agreement, your husband stopped visiting your bedroom. Every night you passed by the dark panelled oak of his door, dulled with the passing of time. You hated the sound of the sharp click as it closed behind him.

I see you, Mrs Bennet. I wish I knew your first name.

Yours affectionately

Orla

An evening with Claire Keegan, author of ‘Foster’

Last night, I attended a reading and Q&A with Irish author Claire Keegan. This event was part of the Well Festival of Arts and Wellbeing, which is in its fifth year here in Waterford city and county.

Author Claire Keegan

Claire is the author of two books of short stories and a novella called ‘Foster’. All her books have received prestigious awards, too numerous to mention, and ‘Foster’ is on the syllabus for Leaving Certificate English.

With only three books, she has become a giant in the world of literature in English, and deservedly so.

I last saw Claire at a seminar in Cork city in 2010. That was an event I have remembered ever since. She spoke then for hours, almost without a break, weaving a spell with her words, both spoken and read. I couldn’t help but take lots of notes as everything she said rang so true with me. I refer back to those notes to this day.

Last night, we were treated to a reading from ‘Foster’ – an extract in which the central character, a child, describes her first day with her new, ‘foster’ parents. The author’s musical voice and expressive face enhanced the reading. I didn’t want her to stop.

Then for the audience Q&A. Unmoderated Q&A sessions can veer dangerously into time-wasting territory. By that I mean both the other audience members’ and the author’s time. Claire handled questions on all stages of the spectrum with grace and calm. She is (in?)famous for not taking any shit and it is a deserved reputation. For this we, the audience, have to thank her because an author who can deal respectfully with time-wasters and move on quickly is creating time for useful discussion, which benefits us all.

Remarks by Claire that have stuck with me are as follows (this is based on memory – if there are inaccuracies or omissions, please post a comment below):

- Claire writes slowly, going back to the start of the previous day’s work, dredging out extraneous material until she has a work she is happy with.

- Characters are defined by how they spend their time. Claire reminded us that we have limited, precious time on earth. What each of us does with that time says everything about who we are.

- “A good middle” is the hardest and most crucial part of a work. Once you have a good middle, your ending will emerge.

- Desire is another key driving force behind each character. What does he or she desire? Find out.

- Echoing Tolstoy’s remark that “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way”, Claire pointed out that happiness does not usually make for great fiction (this is my interpretation – Claire did not use this quote). She highlighted loss as a driving force in fiction.

The event ran to just over an hour, which gave the audience a short and very sweet distillation of Claire’s writing wisdom and a beautiful reading.

My thanks go to the organisers of the Well Festival of Arts and Wellbeing, and the staff of Tramore Library for the welcoming, professional manner in which they hosted the event.

Cork International Short Story Festival 2017

I was in Cork city at the weekend for this year’s Cork International Short Story Festival. This festival started out as the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Festival has been running for 17 years.

One of the events that I attended was a panel discussion on ‘The short story – the state of the art’. Tania Hershmann chaired (standing in for Eimear Ryan) and the panel consisted of Nuala O’Connor, Danielle McLaughlin, Tom Morris and Rob Doyle.

I was very keen to hear this discussion as I chaired a panel – that also included Nuala and Tom – on the same topic for Waterford Writers’ Weekend in 2014.

L-r: Tania Hershmann, Danielle McLaughlin, Rob Doyle, Tom Morris, Nuala O’Connor.

As you would expect from a panel of this calibre, the discussion was hugely insightful and interesting. Tania Hershmann did an excellent job of chairing and making sure that the discussion was well balanced between positive and negative points. Highlights for me were as follows (note that these are my impressions, not a comprehensive account of the event):

Nuala pointed out that we are lucky in Ireland to have a thriving culture of both literary journals and small presses, both of which are good news for emerging and ‘non-mainstream’ writers. She also made that point that it is a positive that our literary critics are interested in the short story and give it column inches.

One thought-provoking observation by Nuala was how regrettable it is that women’s magazines no longer publish short stories. These magazines used to be an important outlet for short fiction. It is also a pity for the form that when short stories are published in mainstream magazines such as the RTÉ Guide (Ireland’s most popular TV publication, which reaches 80% of Irish homes), they tend to be written by authors who are not specialists in the form, such as novelists who have been asked to write a short story. The outcome can be that the short stories that reach a mainstream readership through these magazines are not necessarily of the best quality, not the best examples that the form has to offer.

Tom made some interesting points about the tone of discussions about the short story at writing festivals. The approach, he said, is often disappointingly basic, with questions like “What is a short story?” and “How long should the short story be?” The short story is sometimes spoken of as if it were the post-colonial ‘other’ to the novel, which tends to objectify and restrict the form.

One thing that particularly caught my attention was Tom’s point that short story collections can ‘lock up’ our work. In other words, once a story is published in a collection, it can be stuck there, with no other route to reach audiences. Tom cited his own initiatives of “Out of office stories” (where interested parties send an email to a special address that Tom has set up and in return they receive an out of office reply with a story attached) and “A small, good thing” (where subscribers receive a short story selected by Tom). He also mentioned Twitter as a medium that writers can use in a variety of ways to reach wider audiences.

Danielle McLaughlin is a writer that I was not familiar with, though I had heard of her book Dinosaurs on other planets, which has been making waves recently. Danielle founded and runs a monthly writers’ event in Cork city called ‘Fiction at the friary’. She made the point that the practice of reading fiction aloud in embryonic forms – first drafts, second drafts and so on – can be refreshing and inspirational for both writers and listeners. Danielle also touched on the subject of the tone of discussions about the short story. As an example, she quoted the phrase “The traditional Irish short story”. Whose tradition, she asked, is being referred to here? She emphasised the importance of challenging clichés about the form.

Rob Doyle took up the point about ‘iconic’ short stories and their influence on writers. While he admires Chekovian examples of the form, he said, he finds inspiration in more experimental short fiction. He cited Jorge Luis Borges, David Foster Wallace, Jhumpa Lahiri and June Caldwell (whom I spotted outside having a cigarette; her new book Room little darker (see picture at the end) is getting brilliant reviews). The name George Saunders came up – I think Nuala mentioned him – as a popular writer whose work is more in the experimental vein, as did Lucia Berlin, a short story writer who has been called “one of America’s best-kept secrets”, and Arlene Heyman, who has a new book out about sexuality among older people called Scary old sex.

There was also an interesting question from the audience about the fact that short stories are read and studied in Irish schools. People who went through the Irish education system in the 1970s and 80s will remember the textbooks Exploring English and Soundings, which contained gems of short stories like ‘My First Confession’ by Frank O’Connor and ‘The Widow’s Son’ by Mary Lavin. Some panelists agreed that their love of the form was influenced by their exposure to stories like these in school, although as I said above, Rob expressed a preference for more experimental examples of the form.

I always try at festivals to get to know the work of (to me) new writers. Rob Doyle chaired a reading and discussion with two writers whose work I was unfamiliar with: Tanya Farrelly and Sean O’Reilly. Tanya is the author of two books: When the Black Dogs Sing and The Girl Behind the Lens. Her reading was really entertaining and a pleasure to listen to.

Tanya Farrelly reading. Seated: Rob Doyle, Sean O’Reilly.

She read at a good, slow pace and did justice to the large amount of dialogue in the extract. I am always struck at readings by how important it is to emerging writers to be good public speakers. We don’t write our work for it to be read aloud, but we are often called upon to do exactly that. Like any skill, some are more gifted with it than others. Sean was also entertaining to listen to, but he read too quickly. This, combined with the seemingly large number of different characters in his extract, made his reading hard to follow.

Sean O’Reilly reading. Seated: Tanya Farrelly, Rob Doyle.

Despite this, my interest in his work was piqued. His most recent book, Levitation, is published by Stinging Fly.

I came out of these two events feeling really pleased that I had attended. And what brilliant value for money at €5 per event! Kudos to the festival organizers, the Munster Literature Centre (represented at both events above by its administrator, Jennifer Matthews).

My post-event happiness was tempered only by the discovery that I had only €35 with me and so I had to restrict my purchases at the sales table in the foyer to only three of the many books on offer: Joyride to Jupiter by Nuala O’Connor (which she signed for me), the Summer 2017 issue of The Stinging Fly and Room Little Darker by June Caldwell (I looked for her to sign it but she had gone).

My book haul from the festival.